The Story

After a punishing first day of battle on December 15, 1864, the Confederate army pulled back to a shorter battle line more than two miles south, roughly stretching east-west along what is now Harding Place and Battery Lane. Each end of the line was established on a prominent hill – on the western flank, Compton’s Hill (later, “Shy’s Hill”), and on the east, Overton’s Hill. The latter was part of the 1,050 acre plantation of Col. John Overton II, whose house, Travellers Rest, had been used by Gen. John Bell Hood as a headquarters during the Nashville campaign. It was more commonly known in the community as “Peach Orchard Hill.”

Defense of the eastern flank was assigned to the corps of Confederate Lt. Gen. Stephen D. Lee, 31, a West Point graduate who went on to become the first president of Mississippi State University. The two divisions of Lee’s Corp were under the command of Maj. Gen. Carter Stevenson and Maj. Gen. Henry Clayton. Their exhausted troops dug in around the high ground during the night and early morning hours following their retreat from the area around Granbury’s Lunette the day before. Lee had some 28 field artillery pieces. They could not be fully utilized during the day due to a shortage of ammunition, but at close range, they were devastating when combat erupted late in the afternoon.

First light on Friday, Dec. 16, brought another rainy, misty day as Federal forces began to amass north of Peach Orchard Hill. The eastern wing of the Union line was assigned by Commanding General George Thomas to Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Wood, a 42-year-old West Pointer who was a career U.S. Army veteran. His IV Corps consisted of Brig. Gen. Washington Elliott’s Second Division, Brig. Gen. Samuel Beatty’s Third Division, and Maj. Gen. James B. Steedman’s Provisional Detachment.

The men of Lee’s Corps were exhausted from Thursday’s fighting and the all-night repositioning and effort to throw up defensive works, including felling trees and other obstructions for abatis in front of their lines, as they watched the impressive blue array of Wood’s Corps assembling to their north. Federal artillery began a relentless pounding of the Confederate positions in the early morning and continued the heavy barrage most of the day, causing injury to troops and damage to defensive works, horses and morale.

Questionable decisions. As the day wore on, officers on both sides made unwise decisions that later proved to be costly. First, Gen. Hood became worried about the artillery bombardment sounding from the east, and decided to pull two brigades from Cleburne’s Division (Gen. James A. Smith) defending the southwest slope of Shy’s Hill – Lowery’s and Granbury’s — to reinforce Clayton’s Division at Peach Orchard Hill. At the end of the day, Lee’s Corps had handily won the field of battle at Peach Orchard and could have done so without Cleburne’s two brigades, which in hindsight were badly needed on the hard-pressed Confederate left.

Second, on the Union side, Gen. Wood also made a questionable decision, one that proved to be as critical, and ironically similar to, the devastating decision made by Gen. John Bell Hood 17 days before when he ordered an open-field assault on the entrenched Federal line in Franklin on Nov. 30. Wood had met with his Commander, Gen. Thomas, around mid-day near Franklin Pike, and was told to keep the eastern flank of both armies occupied during the day while the main Federal force maneuvered into position to attack Confederate defenses on and around Shy’s Hill a little over two miles to the west. According to James McDonough in Nashville: The Western Confederacy’s Final Gamble, Thomas told Wood the plan of battle was similar to the day before, “to outflank and turn (the Confederate) left, but then added that Wood should be “constantly on the alert for any opening for a more decisive effort, but for the time to bide events.”

Wood, for his part, appears to have taken the opening of the last statement as permission to pursue an attack rather than as an order for a diversionary engagement, and he did so. Following consultation and reconnoitering involving 2nd Brigade Col. Sidney Post, Wood’s Corps began assembling for an afternoon assault on the Confederate right.

The obstacles facing the Union assault were formidable. Between their lines and the Confederate troops dug in behind breastworks along the high ground of the Hill were several hundred yards of wide-open terrain. The Union troops would be required to cross cornfields and other open unobstructed ground, leaving them completely exposed to Confederate fire. Even worse, footing was hazardous in the mud caused by recent rains and the thaw from the previous week’s deep freeze; boots were bogging down, slipping, or getting caked in mud. All of this muddy, exposed advance would occur uphill toward the 300-foot elevation of the Hill. The base of the Hill bristled with the web of branches of felled trees creating the abatis, which presented a final obstacle to gaining the parapets of Lee’s Corps. The wide-open field of attack was broken by only a single dense thicket of trees and brush, like a small “island” in the cleared ground.

On a smaller scale, the setting was eerily similar to Hood’s exposed assault on Franklin, and in the end, the Federal assault turned out to have a result similar to the one experienced by Hood’s Army in Franklin – the Union forces suffered their worst defeat of the Battle of Nashville, including more casualties than any other skirmish in the battle, numbering by some estimates in battle reports as high as 1,500 – 2000 men dead or wounded.

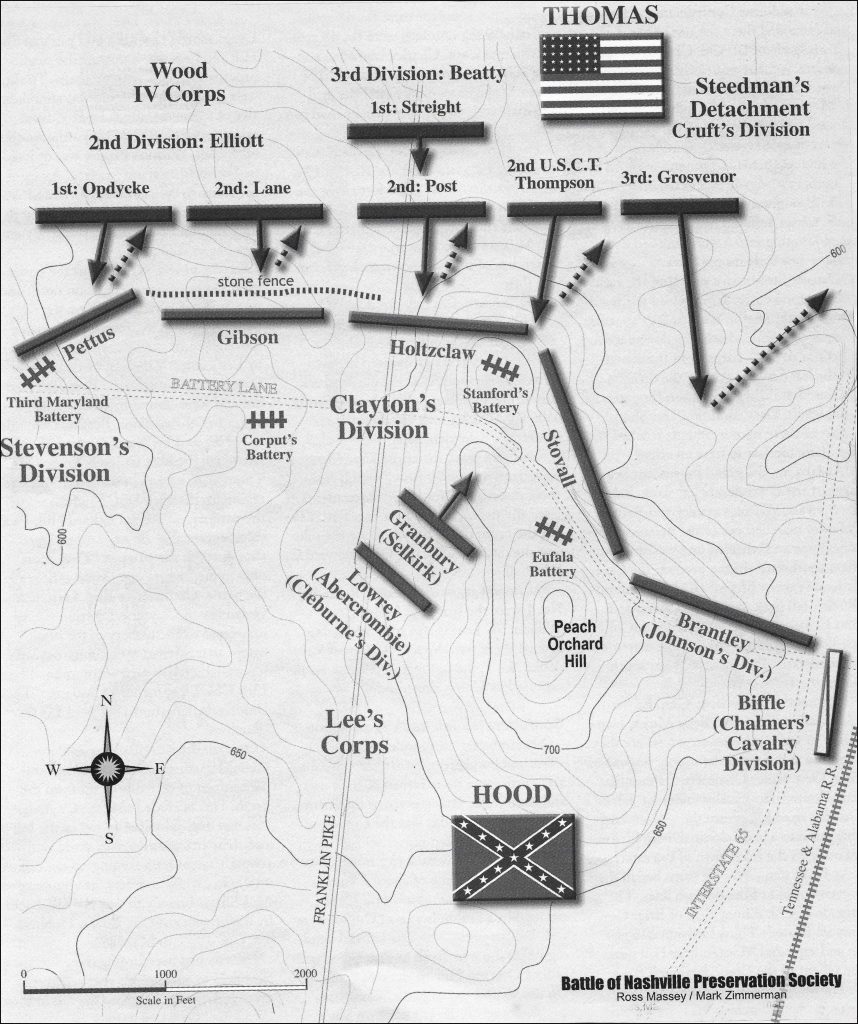

Above: Map courtesy of Guide to Civil War Nashville, a comprehensive tour guide to the Battle of Nashville sites. Maps created by author Mark Zimmerman in conjunction with historian Ross Massey. First published in 2004, the 2nd edition was published in 2019. Click here for more information.

The battle begins. At about 3:00 p.m., the stage was set. As the Union forces began to advance southward, the first wave of assault was led by Post’s brigade, which was in the middle of the Union line and virtually following the Franklin Pike as it ascended southward toward Confederate positions on the high ground. The Alabama brigade of Brig. Gen. James Holzclaw was directly in front of Post’s advance, also partially arrayed across the Pike along with other units in Clayton’s Division.

Farther to the east, the confrontation took on another level of historical significance, because the division led by Steedman consisted primarily of black troops, most of them not long-removed from slavery and having minimal, if any, combat experience. The African American troops, part of the United States Colored Infantry Regiment which had been organized in 1863, made up three regiments within the 2nd Colored Brigade commanded by Col. Charles R. Thompson – the 12th, 13th and 100th United States Colored Troops (USCT). To Thompson’s left was the 3rd Brigade of Col. Charles Grosvenor, which included the 18th USCT regiment.

Waiting for them on the high ground was the Georgia brigade of Confederate Brig. Gen. Marcellus Stovall, with Holzclaw to his west, the two lines forming a corner pointing towards the attacking force.

The assault began with Post’s brigade in the front line, followed by the 1st Brigade of Beatty’s division, commanded by Col. Abel D. Streight. Post’s line was about 40 yards ahead of Thompson’s black regiments. Defensive fire was so devastating from the Confederate lines that the attack was already beginning to falter early when a canister shot hit and killed Post’s horse and seriously wounded Post himself. The wound took Post out of the action, and he went on to be awarded the Congressional Medal Of Honor. Some of Streight’s troops managed to get close to Holzclaw’s works, but their advance could not be sustained.

USCT Joins the fight. To Post’s east, a “battle within a battle” was occurring on the Union eastern flank. As the all-white troops of Generals Holzclaw and Stovall looked out and down upon the advancing blue wave, they could see that Steedman had sent three regiments of African American troops, the 12th and 100th USCT in the front, with the 13th USCT following in the second line.

Above: The graves of many of the men who died at Peach Orchard Hill surround this 9-foot bronze statue in the Nashville National Cemetery, dedicated in 2003 to “the 20,133 who served as United states Colored Troops In the Union Army.” (Photo by Tom Lawrence for BONT)

Above: The graves of many of the men who died at Peach Orchard Hill surround this 9-foot bronze statue in the Nashville National Cemetery, dedicated in 2003 to “the 20,133 who served as United states Colored Troops In the Union Army.” (Photo by Tom Lawrence for BONT)

Numerous accounts of the battle note the relish with which the Confederate troops awaited the advance of the black soldiers, who were so exposed they were virtually target practice for the Confederate veterans on high ground. Angered by the day-long cannonade from Federal artillery, as well as the presence of the brigade of Union soldiers who were African-American, the fire from the Confederate defenses was withering. The assaulting troops themselves were virtually devoid of military experience. The 12th and 13th USCT had seen minimal combat action at New Johnsonville, but the others were seeing their first combat.

The isolated thicket of trees standing alone in the cornfield led to further problems. It was in the pathway of the 12th USCT, and as they were filing around it in double-time, other units mistook their speed as a “charge,” and launched an unplanned advance. The confusion caused the uniform lines of the multiple units, including those within both Post’s and Thompson’s brigades, to become confused and bunched up, and they were devastated not only from the frontal fusillade from the Confederate line, but from enfilading fire into the flanks as well, some of it by the voluminous canister and shot from the field guns on Peach Orchard Hill.

Even after Post’s brigade as well as the first two USCT lines were forced to fall back across the field of engagement, which was by then was covered by a fine mist of rain and thick smoke of the artillery cannonade, the 13th USCT continued their assault up the hill and through the abatis, getting close enough to the parapets that five flag bearers were killed in their desperate effort to save their colors. Gen. Lee noted in his report that his troops had “reserved their fire until (Union troops) were within easy range, and then delivered it with terrible effect.” The 13th USCT paid the price of this strategy.

Praise for black troops. Post-battle reports from both armies spoke of the extraordinary courage of the soldiers within all of the black regiments, but particularly the 13th USCT, as they forged ahead, knowing that their chance of victory, even of getting to the Confederate line, was minuscule. Despite their bravery, the 13th unfortunately suffered the most casualties of any regiment on either side of the two days of the Battle of Nashville, with almost 40% of the 556-man regiment killed or wounded.

Since black troops were only recently established, and had been sparingly used throughout the War, there apparently was at that time some question as to whether African American troops would stand and fight under combat conditions. The assault of the USCT soldiers proved the answer. Gen. George Thomas himself, later inspecting the battleground strewn with the bodies of black troops north of the Confederate breastworks, said to his staff, “gentlemen, the question is settled; Negroes will fight.”

Since black troops were only recently established, and had been sparingly used throughout the War, there apparently was at that time some question as to whether African American troops would stand and fight under combat conditions. The assault of the USCT soldiers proved the answer. Gen. George Thomas himself, later inspecting the battleground strewn with the bodies of black troops north of the Confederate breastworks, said to his staff, “gentlemen, the question is settled; Negroes will fight.”

Their division commander, Gen. Steedman, made note of the fact that the black troops took the brunt of the Union assault that day, and concluded, “I was unable to discover that color made any difference in the fighting of my troops. All, white and black, nobly did their duty as soldiers,… such as I have never seen excelled in any campaign of the war in which I have borne a part.” Colonel Thompson’s report noted that “(t)hese troops were here, for the first time, under such fire as veterans dread, and yet, side by side with the veterans of Stone’s River, Missionary Ridge and Atlanta, they assaulted probably the strongest works on the entire line, and though not successful, they vied with the old warriors in bravery, tenacity, and deeds of noble daring.”

And as part of a rare accolade from Confederate officers, Gen. Holzclaw, whose brigade was in the middle of the line, praised the black troops as “gallant,” and noted that even though they were absorbing a devastating fusillade, they continued to advance their line, concluding that the odds were so stacked against them that “they came only to die.”

The battle at Peach Orchard Hill was a resounding victory for Hood’s troops, but it was the only one within the Battle of Nashville for the Confederacy. Even as Confederate troops were celebrating the outcome at Peach Orchard Hill, the western and middle segments of the Confederate line were collapsing from the massive Union assault from the west and northwest. The domino effect swept the entire Confederate line from the field of battle, and Hood’s Army of Tennessee was forced into retreat toward Brentwood and Franklin.

For examples of more comprehensive readings regarding this part of the Battle, see Wiley Sword, The Confederacy’s Last Hurrah (1992); Stanley F. Horn, The Decisive Battle of Nashville (1956), and the more recent fact-filled book by James Lee McDonough, Nashville: The Western Confederacy’s Final Gamble (2004), all of which were used as sources for the summary above.

Visiting Peach Orchard Hill

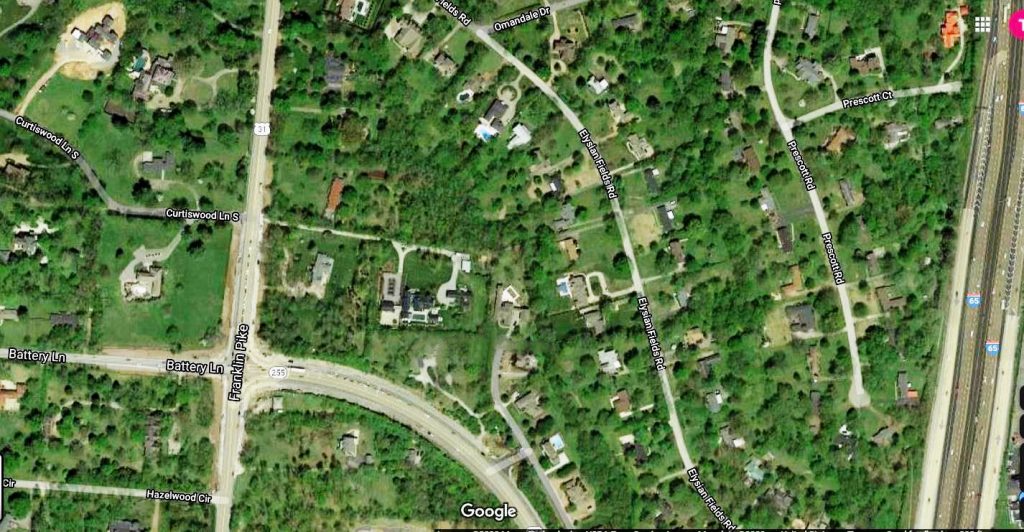

Unfortunately, visiting the Peach Orchard battlefield is only available to the public by car or bicycle. No public areas within the large expanse of the battle ground were preserved as such before it was developed into residential properties. In the late 1960s, Battery Lane was extended as “Harding Place” eastward from Franklin Pike, cutting a deep and wide right-of-way gap through the high ground of Peach Orchard Hill.

To visit and visualize the Peach Orchard battlefield area, a key location is the intersection of present-day Battery Lane and Franklin Pike. The Pike was in existence at the time, but Battery Lane was not. However, Battery Lane generally tracks the Confederate line, from the intersection westward to Shy’s Hill.

Above: Present day Franklin Pike and its intersection with Battery Lane/Harding Place. The northeast quadrant of the intersection was ground zero for the USCT attack. (Click to enlarge)

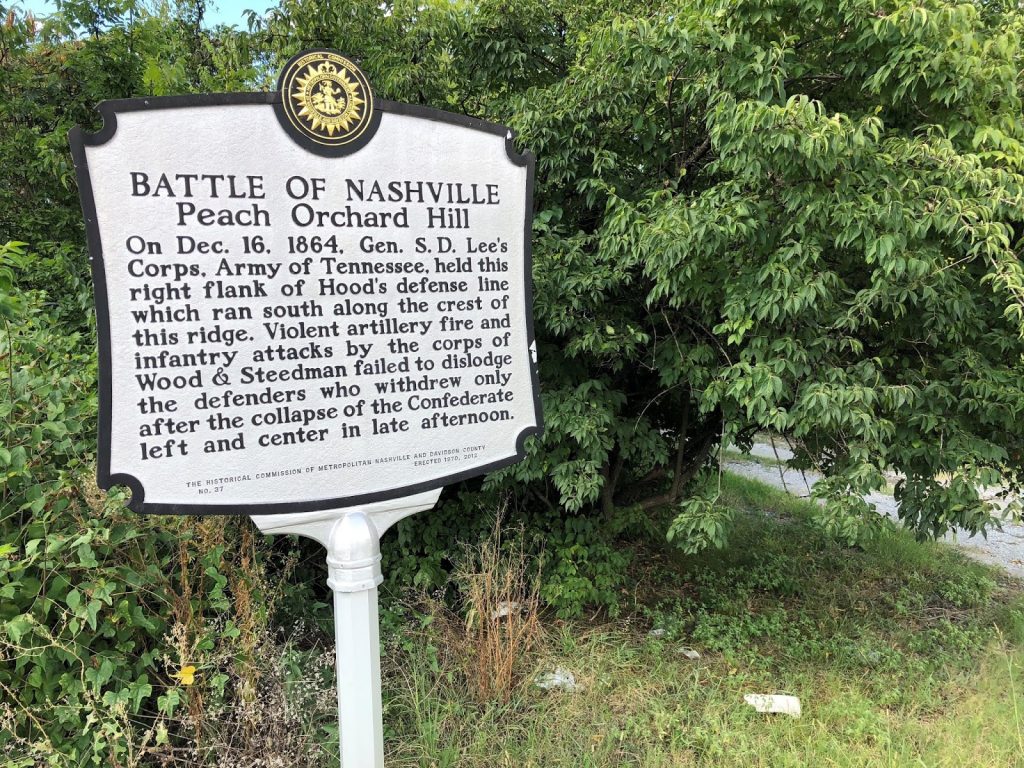

By driving south on Franklin Pike from the I-440 overpass, visitors can roughly follow the line of attack by Federal Col. Sidney Post’s brigade, and can generally imagine Confederate Gen. Holzclaw’s defensive line parallel to Battery Lane, just north of the current intersection of Battery Lane and Franklin Pike. There are two historical markers with identical wording, one located about 200 yards north of the intersection along the east side of Franklin Pike, and another located on top of the hill along the north shoulder of Battery Lane/Harding Place (facing east). [NOTE: The Battle of Nashville Trust did not provide the description on these markers, which were originally placed in 1970.]

The core of the battle occurred upon the northeast quarter of the Battery Lane-Franklin Pike intersection (east of Franklin Pike, north of Battery Lane), with the USCT regiments attacking toward the salient of the hill from the north and northeast. The Battle of Nashville Trust continues in its attempt to locate property to commemorate this portion of the battlefield, but the area is virtually fully developed residentially.

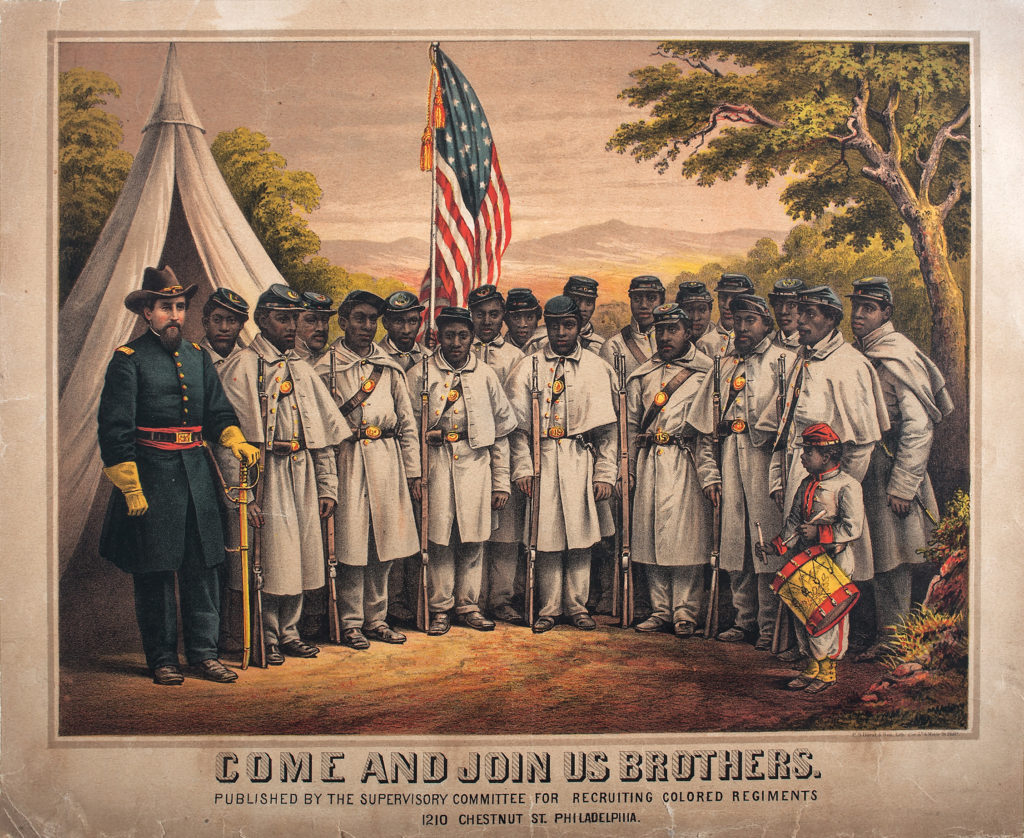

THE STORY OF THE USCT IN NASHVILLE

Following the Emancipation Proclamation, 175 regiments of the United States Colored Troops were created beginning in January, 1863, and eight of those units fought in the Battle of Nashville. In the February, 2013 edition of Civil War Times, historian and author Noah Andre Trudeau published an article describing these units and their experience in Nashville, including the deadly but courageous attacks up Peach Orchard Hill. Click on the photo of the recruiting poster below to read his article, as later published online at HistoryNet.com:

Above: Early recruiting poster for United States Colored Troops. Click photo to read about the USCT’s history during the Battle of Nashville

Above: Early recruiting poster for United States Colored Troops. Click photo to read about the USCT’s history during the Battle of Nashville

Below are quotes utilized by USCT author Noah Andre Trudeau to illustrate the USCT in Nashville.

Capt. Henry Romeyn, 14th USCT:

“Camp was astir at 4 a.m., and breakfast had been eaten long before daybreak. One hundred rounds of ammunition per man and two days’ rations were issued, and just as the first grey streaks of dawn appeared, the companies ‘fell in,’ leaving tents standing.”

Capt. Henry V. Freeman, 12th USCT, just before the attack at Peach Orchard Hill:

“It was probably their strongest position. The slope of the hill was obstructed by tree-tops. The approach was over a ploughed field, the heavy soil of which, clinging to the feet, greatly impeded progress.”

Rebel gunner on Peach Orchard Hill:

“On they came in splendid order, banners flying, mounted officers with drawn swords careering up and down in front of the lines. Then our artillery had its opportunity.”

New York Times correspondent Benjamin C. Truman:

“The rebel infantry blazed away at a fearful rate, and the artillery discharged sixteen shots of canister, which made the assaulting column reel, waver, and almost fall back.”

Alabama soldier, describing the USCT attack from his position on the Hill:

“There were very few negroes who retreated in our front, and none were at their post when the firing ceased; for we fired as long as there was anything to shoot at.”

Capt. Henry Romeyn, 14th USCT:

“(T)he ground [was] strewn with dead and wounded as thickly as a farmer’s field with sheaves of a more peaceful reaper.”

Capt. Henry V. Freeman, 12th USCT, recalling the attack later in 1888:

“Who will say that men who fought and suffered as did these colored soldiers have not fairly earned for themselves and their race the freedom which the war gave them?”

Col. Thomas J. Morgan, 14th USCT, writing in 1885:

“I cannot close this paper without expressing the conviction that history has not yet done justice to the share borne by colored soldiers in the war for the Union.”

Sgt. Maj. Daniel W. Atwood, 100th USCT:

“It was the first time in the memorable history of the Army of the Cumberland that the blood of black and white men flowed freely together for one common cause for a country’s freedom and independence. Each was cheered on to victory by the cooperation of the other, and now, as the result, wherever the flag of our love goes, our hopes may advance, and we may, as a people, with propriety claim political equality with our white fellow-soldier and citizen; and every man that makes his home in our country may, whatever be his complexion or progeny, with propriety, exclaim to the world, ‘I am an American citizen!’ I ask, is there not something in this over which to rejoice and be proud?”

Historians Tell The Story

Because this part of the battlefield is so difficult to visit and envision, BONT has made the following audio-video interviews and podcasts available to help visitors understand the facts, terrain and meaning of the battle at Peach Orchard Hill:

Military Expert Explains the “Killing Field”

The video below features BONT President Jim Kay and retired Lt. Col. James P. Reese, a 25-year Army veteran who served with distinction with the elite special ops unit Delta Force, discussing the USCT charge against Confederate defenses at Peach Orchard Hill, and why it became “a killing field.”

JIM REESE AND JIM KAY TALK ABOUT ATTACK … at Peach Orchard Hill at Battle of Nashville on Dec. 16, 1864.

Posted by Battle of Nashville Trust on Monday, June 22, 2020

John Banks’ Civil War Blog: Rare Visit To The Hill

John Banks, a member of the Battle of Nashville Trust Board of Directors, is an author and Civil War historian who created the video blog below from private property on the slope of Peach Orchard Hill. The USCT regiments charged up this ground in a storm of fire from the Confederate line above them. The photo is looking north, with Franklin Pike in the distance. In the late afternoon of December 16, 1864, this was a killing field. To hear John’s description, click on the photo.

The video above is embedded within an excellent overview of the battle, highlighting the involvement of the United States Colored Troops at Peach Orchard Hill. Click on photo below of USCT grave markers in Nashville National Cemetery:

John Banks’ Civil War Blog, “Came only to die.”